The Hamilton Spectator – September 26, 2015

A WIDE range of individuals and organisations provided testimony to a Hamilton hearing of Victoria’s parliamentary unconventional gas inquiry on Wednesday.

The individual speakers were local members of a variety of anti-gas groups or alliances, though they had varied opinions on whether the industry should be subject to an ongoing moratorium, a permanent ban, or rigorous regulation that favoured agriculture.

Mineral exploration company Mecrus Resources provided testimony on a potential oil shale deposit in south-west Victoria.

Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation testified about its difficulty in managing native title agreements with gas companies.

Wannon Water gave testimony that it had not completed its own assessment of likely surface and ground water impacts from a gas

industry.

Lowan MP Emma Kealy told The Spectator that she was “surprised that the inquiry was originally not going to have a hearing in south-west Victoria, given all the exploration licences we have in the region”.

“I fought hard for a local hearing and that was worthwhile given the

large turnout,” she said.

“It was also an opportunity for myself to hear from local farmers, especially towards the end of the hearing when they spoke of their passion for the land and their views and concerns about unconventional gas.”

‘Risks not fully understood’: Mayor

HAMILTON’S State Government Gas Inquiry hearing

kicked off with an audience of about 40 people from

the local and Portland regions.

At the time of publication, representatives from four local governments had given testimony about a potential onshore unconventional gas industry on Wednesday.

A representative from Glenelg Shire said there was a concern that the industry would result in a reduction in environmental standards and risk to water and might damage the region’s green image.

Southern Grampians Mayor Peter Dark said that he shared those concerns and pointed to two separate motions passed by councillors that backed the “importance of protecting food, fibre, water aquifers”.

“In June 2015 The Southern Grampians Shire Council formally declared itself a gasfield free region due to community concerns,” he said.

“There is possibly a significant risk to agricultural

productivity.”

“The risks are not fully understood.”

Cr Dark said Southern Grampians was “dependent on agriculture” as it was the sector that provided the largest source of employment.

He said that the region had higher value per hectare than many other areas and “we have half a million hectares in agricultural production”.

“Southern Grampians Shire has invested heavily in a land use study to diversify local agriculture,” he said.

“We have untapped potential; we are well-placed to continue to support global food production with all the conditions to be a significant player.

“We have an obvious natural advantage: groundwater. The impact of gas needs to be considered.”

Cr Dark said that, compared to the “10/15 year lifespan of a gas field”, the “potential adverse impacts have a much longer lifespan”.

“The royalties paid to the State Government are potentially much less than the cost of damage,” he said.

Cr Dark’s testimony was met with a “hear hear” from

some in the audience.

A representative from Conrangamite shire said that the region’s existing onshore conventional gas plants provided significant employment.

He said that Conrangamite was one of the few areas that had “direct experience with onshore gas” and non-hydraulic fracturing operations “should be exempt” from the current moratorium.

“It is difficult to make informed decisions unless we know that the resource exists,” he said.

The Corangamite representative also said that there was a risk of the existing local gas operations could be put at risk by getting caught up in the push against unconventional gas.

A mineral exploration company, Wannon Water, local farmers and an anti-gas activist group were scheduled to give testimony at the hearing.

The human cost to farmers

SOUTH-WEST Victorian farmers have all spoken against the prospect of a new onshore unconventional gas industry, giving extensive and at times emotional testimony to a gas inquiry hearing in Hamilton on Wednesday.

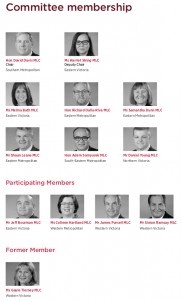

Victorian Parliament’s Environment and Planning Committee, made up of MPs from a wide range of parties, heard from a mineral exploration company, Wannon Water and local Aboriginal traditional owners.

By far the largest number of individual speakers was made up of farmers from around the Hamilton and Portland regions, along with other locals.

Unconventional gas and hydraulic fracturing technology were compared by one farmer with the past industrial contamination scandals of DET and asbestos.

Another farmer said that he and his peers just wanted “to be left

alone”.

Branxholme farmer Colin Frawley said an unconventional gas

industry would “put us at risk”.

“For our livestock, we must have underground water,” he said.

Without groundwater, he said his farming business “would be totally compromised”.

“Gas may be very profitable but we as a farming community have

to carry the risk,” he said

“They will walk away in 10/15 years. We would still be here paying taxes and contributing to the community.”

Mr Frawley described the prospect of fracking as a “marketing nightmare” for the region’s “clean and green image” with wholesale and retail buyers.

After 18 months of fighting the proposal for an onshore unconventional gas industry, signs of wear and tear are staring to show.

Drumborg farmer Gary Everett, who described himself as a “passionate lamb producer”, talked of the “psychological burden” from campaigning.

He said stress had been placed on families and marriages.

Mr Everett primarily talked about his own land, saying his father bought the property 63 years ago and was a “pioneer” in a new community.

“You could buy land, you could buy a house, but you made the

farm and the family home” he said.

“Drumborg is a great community. We are fighting for our survival.”

Mr Everett said he was a member of one of the 67 anti-gas groups across the state, and they were gaining considerable followers on a daily basis.

“Some of us have become dismayed, let down or left angry by people in Government departments, politicians, energy companies, our own farming bodies the VFF and UDV, because for saying this industry can coexist with our farms.”

“This isn’t true.”

He became choked up when talking about the possibility of farmers being arrested for “trying to protect the land for future generation”.

Byaduk farmer Aggie Stevenson told a “story of little girl on a farm” who grew up with clean and fresh food, water and air.

“Someone is threatening to take away all these things, purely

driven by greed,” she said.

“I implore you not to be the villains in the story, be the heroes.”

Eastern Metropolitan Greens MP Samantha Dunn told the hearing that Mrs Stevenson’s story “goes to the heart of the level of anxiety, the psychological burden that is taking its toll”.

Eastern Metropolitan Labor MP Shaun Leane asked Mr Frawley to expand on the marketing issue.

Mr Frawley said he had neighbours that export food to Asia and that “Our point of difference is our image, and it you compromise that, you lose it.”

Mr Everett said that he had consulted with Meat and Livestock Australia, which had told him that the responsibility for meat contamination from petroleum was with the owners.

unconventional gas

in Victoria. Photo: Parliament of Victoria

It has been almost 18 months since one of the first anti-fracking

meetings in south-west Victoria.

The one meeting in Digby saw many others follow and the ‘Lock the Gate’ movement grew from an outsider curiosity to spawning local variants.

Some of those local variants are now apparently trying to assert their independence from the ‘Friends of the Earth’ network of professional activists, possibly to gain more credibility with conservative MPs.

Western Victoria MP Simon Ramsay said during the hearing that he found it “troubling” that there were so many anti-gas groups “running around with different agendas”.

Along with committee chair David Davis, Mr Ramsay appeared to have difficulty at times with establishing the organisational and financial structures of various anti-gas groups and regional alliances, as well as their core beliefs.

Eastern Metropolitan Liberal MP Richard Dalla-Riva said the testimony given on Wednesday was similar to that from Gippsland but in Hamilton he had been given the “most detailed, real world example” of potential

agribusiness impacts.

It has been almost two years since the State Government’s ‘Independent Gas Market Taskforce’ report, now colloquially referred to as the ‘Reith report’, which recommended that Victoria “proactively” seek

onshore unconventional gas development.

With about a year to go before an election, the then-Victorian Coalition Government played down the report and recommitted to an industry moratorium.

Aboriginal owners not informed of fracking

GUNDITJ Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation was forced to renegotiate a prior Native Title Agreement due to a gas exploration company not mentioning that it planned to use hydraulic fracturing.

Gunditj Mirring chief executive Damein Bell told a Hamilton hearing of

Victoria’s parliamentary gas inquiry on Wednesday that the Aboriginal corporation had held a number of meetings and exchanged “hundreds of pages of documents” with an unnamed gas company.

“But nothing mentioning it (fracking),” Mr Bell said.

He told the hearing that the potential for fracking, the controversial gas

extraction technique at the centre of protests against unconventional gas, was only discovered when Gunditj Mirring members read the terms of the State Government exploration permit.

“The only reason they had to consult with us was the Native Title Act; I don’t know how they would have negotiated if they hadn’t been forced to.

“The second round of negotiations was friendly, in good faith; we asked why they didn’t mention fracking in the first round.

“They said it wasn’t a public issue back then.”

The inquiry’s committee of MPs asked Mr Bell which gas exploration

company had required a second round of negotiations.

Mr Bell declined and said it was “confidential” but invited the committee

to look up which companies held Petroleum Exploration Permits (PEP) over Gunditjmara land.

Earlier in the hearing, Mr Bell said that the Aboriginal Corporation had successfully negotiated native title land use for exploration in 2013.

Several ‘monthly full briefing’ meetings were then held in 2014 to discuss

the issue of potential fracking on land within the Gunditjmara Native Title

area.

Mr Bell said the purpose of the briefings was to “gather all members to discuss business and make decisions” and said the gas company in question also attended some of those briefings.

The Spectator reported in April 2014 that Gunditjmara People were

to, in the words of Mr Bell, “revisit” their previous native title agreement over shale and tight gas exploration permits in south-west Victoria.

Adelaide-based oil and gas company Beach Energy had a large stake, along with other companies, in two major exploration permits in south west Victoria.

Beach Energy’s 2013 annual report stated that the company “and its

participants were awarded PEP 171 and PEP 150 in Victoria after completing negotiations with Native Title Claimants”.

At the time, a spokesperson for Beach Energy did not deny being involved in Native Title renegotiations but said it was committed to fulfilling its obligations under Native Title.

Mecrus Resources, Somerton Energy, Bridgeport Eromanga Energy, Bass Strait Oil Company Limited and Mawson Petroleum also hold Petroleum Exploration Permits in areas covered by Gunditjmara Native Title areas.

When asked about the status of the Native Title renegotiation, Mr Bell said the Aboriginal corporation was “taking advantage of current moratorium” on onshore gas and the dispute resolution process was still open.

Eastern Metropolitan Greens MP Samantha Dunn asked Mr Bell if all extraction techniques should be included in native title negotiations.

Mr Bell said negotiating parties “shouldn’t hide that from one another”.

The gas inquiry committee was itself the subject of another complaint from Mr Bell.

Mr Bell said he was “extremely disappointed” that the inquiry’s interim report, which was handed down on September 1 this year, contained “no references to traditional owners”.

Inquiry committee chair David Davis MP said that it was only an interim report and that the committee “will have more to say” in the final report.

Mr Davis asked Mr Bell how indigenous views could be adequately represented in the report.

Mr Bell said that Native Title holders were the “first port of call” for new

industrial developments but the State Government process needs to provide opportunity for comment from Indigenous people.

He noted that Native Title holders could be taken to national arbitration, or be subject to overrides from the State Government, if companies accused them of negotiating in bad faith.

Northern Victoria Shooters and Fishers MP Daniel Young asked Mr Bell how the State Government could override native title holders.

Mr Bell said the Government had to “prove that they will not destroy our land” but Indigenous people “have no guarantees”.

Inquiry told further studies

needed in risks to water

WANNON Water has told a Hamilton hearing of Victoria’s parliamentary unconventional gas inquiry that it has not done its own assessment of the risks from a proposed onshore drilling and fracking.

A committee of MPs was told that State Government would most likely be left liable for cleanup costs if something went wrong with water supplies and the gas company responsible was unable to pay.

Branch manager of asset planning, Peter Wilson, told the hearing that a Victorian Government report had found a “low risk of aquifer depressurisation”, a low risk of water contamination, and a low risk of land subsidence from potential gas development.

Mr Wilson did say there was still “considerable uncertainty” due to “limited data availability” and risks to ground and surface water “need to be further studied”.

“The region is highly variable and some sites may have an unacceptable risk, particularly if community drinking water is present,” he said.

Gas inquiry committee chair David Davis MP asked what consultation had occurred between Wannon Water and gas exploration companies. Mr Wilson replied that he had “been in the role of planning for 15 years and been never approached by gas company”.

Eastern Metropolitan Labor MP Shaun Leane asked if the use of steel and concrete well casings could prevent cross contamination between saline and fresh aquifers.

Mr Wilson said that “concrete is a very robust material, considered to be best practise” but he would not say whether it would last indefinitely.

Northern Victoria Shooters and Fishers Party MP, Daniel Young, asked if the issue of well failure could apply to ordinary water bores as well.

Mr Wilson said it could but the “ramifications were different”.

“Linked wells won’t destroy the water resource with salinity, but things like introducing chemicals unfit for human consumption will,” he said.

Mr Wilson also said Wannon Water does not have a direct role in applications for drilling under Victoria’s mining and

petroleum acts.

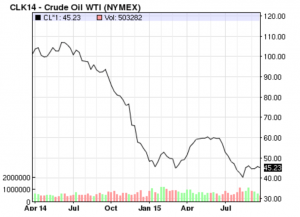

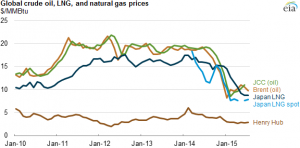

360 million barrels under western Victoria

SOUTH – WEST Victoria’s oil shale deposit is between 15 and 30 times thicker than commercially viable deposits in the United States, according to mining exploration company Mecrus Resources.

Mecrus Resources believes there is a deposit of 360 million barrels of oil contained within its two exploration licence areas between Casterton and the South Australian border.

The company’s ultimate plan to develop the deposit would see a total of 16 wells drilled on a single site about one hectare in size.

These wells would go down 2500 metres to access the oil shale, which is believed to be contained in a layer that is 1500m thick.

Horizontal drilling would be used, with side wells trailing off between two and 3.5 kilometres in any direction.

If one of these sites were successful, then Mecrus could “clone” the operation for “multiple” potential oil deposits thought to be in the region.

These new details were contained in spoken testimony to Victoria’s parliamentary inquiry into unconventional gas, which held a hearing in Hamilton on Wednesday.

Mecrus Resources managing director Barry Richards told the inquiry committee of MPs that Mecrus was a private company that was not obliged to give public statements, but it wanted to engage with the community.

The Spectator reported on Tuesday that a written submission from Mecrus to the inquiry stated that the “prospectivity” of the south-west Victoria deposit was “beyond doubt”.

Mecrus indicated that the deposit could produce $600 million in royalty payments to the State Government over 40 years, putting its commercial value at up to $6 billion.

Almost all the information that Mecrus provided to the inquiry has been in relation to a potential oil shale deposit contained with an 1500 square kilometre exploration region between Strathdownie and Lake Mundi, about 10km west of Casterton.

Mecrus senior petroleum consultant, Dr Rodney Halyburton, told the hearing that the oil shale industry in the United States “got very excited” when they found deposits of between 50 and 100 metres in thickness.

Dr Halyburton said the company’s assessment, along with an independent

study, of the potential deposit was “based on very conservative numbers”.

He said the study was “focused primarily” on a well drilled in 2006 that was the “only onshore well in Australia” that had been producing oil shale, and he found it “amazing” that oil had started flowing from the test well while it was being drilled.

Mr Richards also said the company’s report on south-west Victoria was “conservative, but it does indicate significant resources in our area”.

Eastern Metropolitan Liberal MP Richard Dalla-Riva said the inquiry had previously heard from areas in Victoria with “lots of population, lots of dairy,” but not so much over near Casterton.

“I’m not talking any disrespect to be people over near South Australia; it seems to me that that’s an area where it may have limited impact. Could that happen in this area?” Mr Dalla-Riva asked.

Mr Richards replied that everything the company had been talking about

at the hearing concerned its exploration permits between Casterton and SA.

He described Mecrus as a “diverse organisation” and a “significant explorer of resources in Victoria” with over 140 employees, a “large percentage” of which were in Victoria.

Mr Richards said Mecrus itself had completed no drilling in south-west

Victoria and its further assessments since gaining the exploration licence were based on soil samples, water samples and ground

surveys. “Our people get out and talk to the landholders,” he said.

“That provides feedback to management and as exploration continues we will make ourselves available to the community.

“We have licences in Victoria that have Native Title negotiations and

agreements in place. We believe we are a very responsible community member.”

Mr Richards said the company had tried to contact various groups about its oil exploration, including the Victorian Farmers Federation, but claimed that emails had not been returned.

Mecrus’s written submission stated that hydraulic fracturing, AKA ‘fracking’, would not be an “enabling technology” for shale oil in south-west Victoria as the rock layers were “naturally fractured”.

However, fracking would likely be used to multiply the oil “recovery factor”, or percentage of oil that can be successfully extracted from the ground.

In response to the committee’s questions about safety precautions, Dr Halyburton said that “fracking has been conducted for 50 years, it’s nothing new”.

“People have to be careful. With cowboys, things can go wrong. But we will do everything according to the book,” he said.

Dr Halyburton said the oil industry had learned to be careful with spillage because accidents at offshore rigs were much more difficult to clean up than at onshore operations.

Eastern Victoria Labor MP Harriet Shing asked if an oil industry would create a net economic loss for agriculture, particularly if the marketing image of prime beef was damaged by the proximity to an oil field.

Mr Richards said “I actually fail to see how our industry would damage other industries.”

“Victoria’s lobster industry is huge throughout the world, yet we have

Bass Strait (offshore gas production).”

When asked who would pay for costs and damages in a “worst case scenario”,

Dr Halyburton said the company would take out “significant insurance” for any oil production operation.

According to Dr Halyburton, rock cuttings and excess gas from any oil project would be “reinjected” into the ground.

Gas could also be burned off in a ‘flare’, but that was not likely to happen and a local landfill would also be needed for some waste.

In terms of water management, Dr Halyburton said “Mecrus

will use proprietary technology” from its wholly owned subsidiary company ‘Desalin8’.

According to Desaln8’s website, the company offers “opportunities for extracting high quality freshwater supplies from poor quality brackish groundwater using In Situ Desalination (ISD) technology”.