REX MARTINICH

Comment

Rising unemployment and declining manufacturing will collide with farmer-driven campaign against unconventional gas, but international markets will play the role of umpire.

The Victorian Liberal National Coalition has announced it will support an “extension of Victoria’s (current) onshore gas moratorium until 30 June 2020”.

It should be noted that the next Victorian state election is scheduled for November 2018, resulting in the policy’s effective length being 19 months (if the Coalition was returned to power).

.@MatthewGuyMP says the Coalition gov will place a moratorium on onshore gas until 2020 if elected @abcsouthwestvic pic.twitter.com/s6kShfFU8U

— Bridget Judd (@BridgetJuneJudd) September 28, 2015

Victoria has a moratorium on most aspects of onshore gas exploration and development, which was originally put in place by the previous Coalition Government and later expanded.

The current moratorium is so broad that it has even halted gas exploration projects that are unlikely to use hydraulic fracturing, such as Otway Basin works proposed by Lakes Oil.

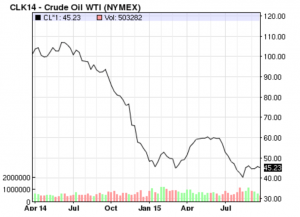

Global oil prices are less than half of what they were 18 months ago, which has placed huge pressure on the US shale oil industry following its fracking-powered boom times.

Many shale projects were given the green light with an expectation that investors would be paid back from oil prices of between $USD80 to $60 per barrel.

Oil prices have spent most of this year between $USD40 and $50 per barrel.

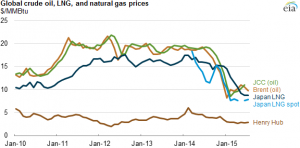

Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) prices were a little slower to follow oil prices but their recent fall has been considerable.

Japanese market regulators even skipped the monthly issue of LNG spot prices in June this year due to “a lack of trades”, a move that was widely interpreted as a sign of “tepid” demand.

The impact of low fossil fuel prices has been felt locally as well, with Adelaide-based oil and gas exploration company Beach Energy cutting $55 million from its capital expenditure budget in January this year.

Beach Energy was also hit by the departure of US energy giant Chevron, which had been a partner for Beach’s joint shale venture in remote South Australia.

The collapse of prices has become its own market-enforced moratorium on new unconventional gas projects, though recent sharp falls in the Australian dollar may help the fledgeling industry.

Meanwhile, an 18-month campaign against unconventional gas in rural areas in the southern half of Victoria, particularly in the rich farmlands of south-west Victoria and Gippsland, culminated in a 1000-strong protest in Melbourne this month.

Wool and red meat prices are rising and so are agribusiness wages, increasing the political clout of farmers and their representative bodies.

The upcoming state by-elections in South-West Coast and Polwarth, combined with over 1700 mostly anti-gas submissions to an ongoing parliamentary inquiry, undoubtedly had a influence in the Coalition’s new gas policy.

The Coalition’s policy appears largely based on the Victorian Farmers Federation policy, which was itself recently strengthened by a conference motion brought by farmers from south-west Victoria.

However, it must not be forgotten that agricultural exports also have floating prices and are influenced by the same global economic slowdown that has helped dragged down gas prices.

If China’s slowing economy results in anxious parents in Beijing and Shanghai no longer paying $AUD60 to $100 for Australian powdered infant formula, then an entire local industry is placed at risk.

If Japan reduces its appetite for premium Australian beef, or executives in Hong Kong take the scissors to business wear budgets, then the effects will be felt locally as well.

Fossil fuels may again dominate the economic stakes thanks to their high price inelasticity, causing large swings from relatively small changes to supply or demand.

The instant economic sugar hit that gas and oil fracking can provide could also be a future godsend for state and federal governments under pressure from rising unemployment and stagnating wages.

The estimates for how long a fracking operation can produce oil or gas varies from between three years and thirty years, but for any government under siege and facing an election that represents a lifetime.

Suffering from an impeding departure of local vehicle manufacturing and uncertainty over where new submarines are to be built, South Australia appears to be hitching its wagon to unconventional gas.

South Australian Treasurer Tom Koutsantonis, a member of a minority Labor Government, tweeted after the Victorian Coalition’s policy announcement that SA was “now the only welcoming jurisdiction for oil and gas investment supplying the Australian east coast markets”.

South Australia now the only welcoming jurisdiction for Oil & Gas investment supplying the Australian east coast markets @APPEALtd

— Tom Koutsantonis (@TKoutsantonisMP) September 28, 2015

Should warnings from petroleum lobbyists come true, and a lack of domestic production does significantly increase local gas prices, then that could also become an election-defining issue for Victoria’s mainly urban population.

Providing that oil and gas companies have sufficient capital and shareholder goodwill, they could ride out the slowdown and return to their non-perishable oil deposits once global prices trend upwards again.

Bargain hunters have also been snapping up shares in oil and gas companies, hoping that their ‘buy in gloom, sell in boom’ strategy will pay off when the oil price rises.

For example, Kerry Stokes bought considerable Beach Energy holdings for as low as 62 cents on the dollar compared to boom times.